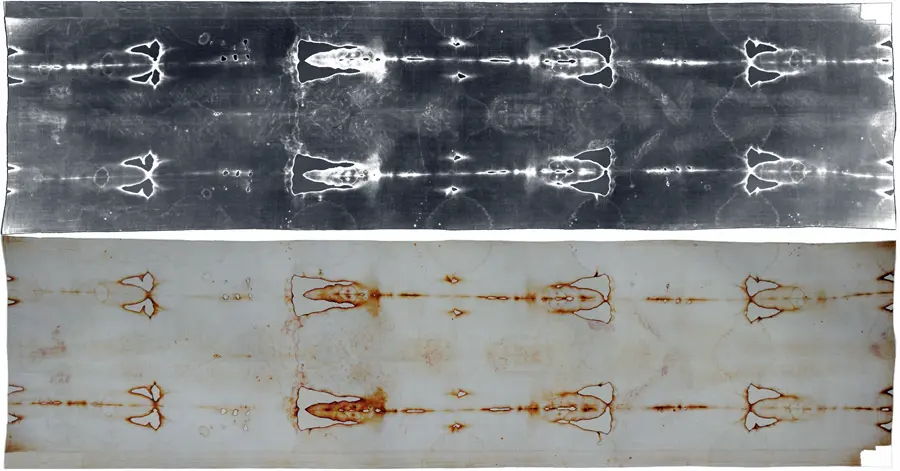

Shroud of Turin full length image on cloth below and its photo on top

The Shroud of Turin: Real Photo of Jesus or Medieval Fake? Debating the Evidence

The Shroud of Turin is an ancient Jewish burial linen cloth used in ancient times by the Jewish people to bury their dead. It is about 14.5 x 3.5 feet or 4.4x1.1 meters in size. On it is a faint, full-body, front and back image of a crucified man (seen in the bottom picture above).

This remarkable relic has been preserved in the Italian city of Turin since 1578 (almost 450 years), which is why it is known as the 'Shroud of Turin'. Millions believe the Turin Shroud is the burial cloth of Jesus Christ and that the image is a real Photo of Jesus - that it is Jesus' face on shroud and that it is proof of Jesus' existence.

The photo at the bottom of the two pictures above, is that of the actual linen cloth as seen by our eyes. The top picture is what the negative of a photo of the original image on the Shroud looks like. This negative of the original image on the cloth shows a clear photo of a noble looking man. Thus the original image on the Shroud of Turin cloth is a negative image.

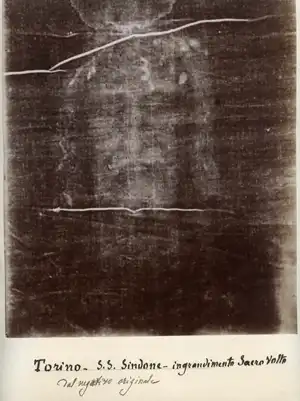

The World-Changing Negative: Secondo Pia's 1898 Discovery

The first photo of the Shroud of Turin caused a global sensation in 1898 when amateur photographer Secondo Pia first photographed it. The image that appeared on his camera's negative was a clear, positive photo of a noble-looking man. This startling discovery confirmed that the original impression on the Shroud itself is a perfect photographic negative. This property remains the Shroud's greatest scientific riddle.

The photo you see here is a copy of the original first photo of the Turin Shroud. It is not as clear as modern-day photography, because the camera used by Secondo Pia was a very large bellows-style camera in the very early days of photography. This first photo taken in 1898 revealed that the image on the Turin Shroud cloth is actually a photographic negative of a man, which stunned the world. The image itself provides a stunningly clear visual of the man's features, despite the primitive nature of the photographic equipment used.

Scientific Riddle: How Was a Photographic Negative Created in the Middle Ages?

The central mystery of the Shroud of Turin is this: Photography was invented only in the year 1826 by French inventor Joseph Nicéphore Niépce using a camera obscura (pin hole camera) with a bitumen-coated pewter plate, requiring an exposure of several hours.

So how could a perfect, full-body photographic negative—with such intricate detail and clarity—be imprinted on linen in the year AD 1260 (earliest carbon date) or earlier? All attempts to reproduce Shroud like image, on pieces of cloth, by many modern day artists, scientists and nay-sayers have failed to replicate the unique characteristics of the Shroud of Turin. The unique image properties of the Shroud continue to defy conventional explanation, making it one of the most studied mystery artifact in the world.

The Carbon Dating Contradiction: The Raes-Rogers Hypothesis

The historical and scientific narrative of the Shroud of Turin is dominated by the contradiction created by the 1988 radiocarbon dating test.

The Original Scientific Finding

The Shroud's verifiable history begins in Lirey, France, between 1353 and 1357. In 1988, a high-profile C14 Radiocarbon Dating test was conducted by three world-renowned, independent laboratories. The results consistently dated the linen to the medieval period, specifically between AD 1260 and AD 1390 (with 95% confidence). This result created a direct contradiction to the Shroud's traditional 1st-century historical claim, leading many scientists to conclude it is a medieval artifact.

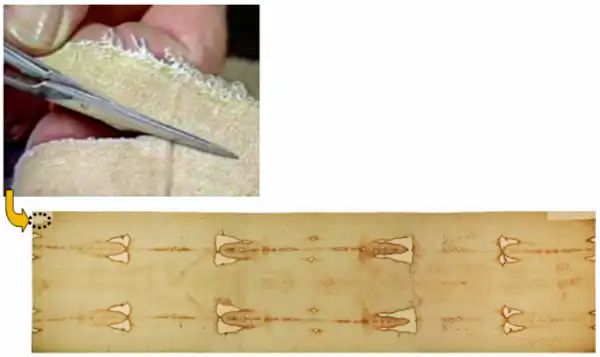

The Fatal Flaw: The Raes-Rogers Hypothesis (Invisible Darning)

The accepted medieval dating was subsequently challenged due to evidence of sample contamination.

The Wrong Sample Area: Medieval Repair

The samples for the 1988 Carbon Dating test were taken from one of the corners of the Shroud. Through centuries of handling and exhibitions, damage was caused to these edges. This damage was repaired using a sophisticated medieval technology known as "invisible darning." This repair involved weaving in new cotton and other threads, which were expertly dyed to match the color and texture of the original linen cloth. Critically, these foreign threads date to the medieval period, not the 1st century.

Conclusive Evidence of Contamination

In January 2005, Dr. Ray Rogers, a retired chemist from the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory and the lead chemist for the 1978 Shroud of Turin Research Project (STURP), published a conclusive article in the peer-reviewed journal Thermochimica Acta.

Dr. Rogers presented irrefutable chemical evidence that the carbon dating sample area was contaminated. His findings proved that the sampled area contained foreign threads that were chemically and structurally different from the original Shroud linen. These threads, introduced during the medieval darning repair, gave the C14 Carbon Test a wrong result by artificially skewing the sample's age toward the repair date (AD 1260–1390). This hypothesis, often referred to as the Raes-Rogers Hypothesis, remains the leading scientific argument challenging the validity of the 1988 Carbon Dating.

Historical Evidence Challenging the C-14 Date

Shroud proponents (those supporting its authenticity) strongly reject the C-14 result, citing concerns about sampling flaws arguing the sample was taken from a repaired and contaminated corner of the cloth that did not represent the image area.

Historical and Art-Historical Evidence for Pre-Medieval Existence

Proponents counter the medieval C14 dating by citing a strong body of art-historical and numismatic (coin) evidence suggesting the Shroud existed well before the 14th century:

1. Art History: The Sinai Christ Pantocrator Icon (6th Century)

The Sinai Christ Pantocrator Icon, housed at St. Catherine's Monastery, is one of the world's oldest surviving painted images of Christ with a beard, dating back to the 6th century (around 550 AD). This icon is extremely significant because it survived the centuries-long periods of "iconoclasm" (image-smashing) in the Byzantine Empire due to the remote, protective location of the monastery in the Sinai desert.

The icon portrays Jesus as the "Ruler of All" (Pantocrator). The most striking feature noted by art specialists is the unique facial asymmetry, which shows a split expression: a stern, judging face on one side and a serene, merciful face on the other. Critically, many scholars believe the icon's facial proportions, wounds, and specific asymmetrical details perfectly align with the trauma and dimensions seen only on the Shroud of Turin's image. This direct link strongly suggests the Shroud was already a known template for Christian artists, centuries before the C-14 dating suggests it even existed.

The icon itself shows a direct link. Its facial proportions, trauma wounds, and unique anatomical details are so precise that scholars believe it is for sure based on the image on the Shroud:

- The facial asymmetry and unique proportions of the 6th-century icon align perfectly with the trauma and dimensions seen on the Shroud's image.

- This suggests the artist copied the unique facial trauma and dimensions seen only on the Shroud's image.

- The Shroud was a known template for Christian art centuries before the C-14 date.

2. Numismatic Evidence: The Justinian II Gold Coin (7th Century)

The Justinian II Gold Solidus coins are historically significant because they were the very first Byzantine coins to feature the detailed image of Jesus Christ, breaking a tradition of only showing the Emperor's portrait. Minted during his reign (685–695 AD), these coins are powerful statements, symbolizing the Byzantine Empire's deep Christian identity. The front of the coin, the obverse, displays Christ Pantokrator ("Ruler of All") looking directly forward.

Critically, the face depicted on this coin in 692 AD is not a generic artistic representation. Shroud researchers have identified numerous unique and unusual characteristics (the large "owlish" eyes, specific beard division, and facial asymmetry) that perfectly match the Shroud's image. This striking correspondence provides powerful numismatic evidence that the Shroud, or its highly influential prototype (the Mandylion), was known and used as the authoritative template for Christ's face over 500 years before the controversial medieval carbon dating suggests the cloth existed.

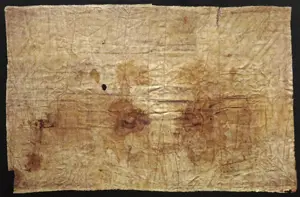

3. The Sudarium of Oviedo (c. 7th Century Documentation)

The Sudarium of Oviedo is a separate small cloth traditionally held to have covered Jesus's head immediately after his death. It has been venerated in Oviedo, Spain, since the 8th century. Forensic analysis reveals that the bloodstains, specific patterns of tears, and dimensions on the Sudarium are a perfect match to the bloodstains and facial dimensions on the Shroud of Turin. This correlation suggests that both cloths covered the exact same body at the exact same time and, critically, links the Shroud's associated relics to a history documented centuries before the C-14 date.

4. The Mandylion of Edessa and the Emergence of the Bearded Christ

The picture here shows King Abgar of Edessa receiving the burial Shroud of Jesus, folded four times to form the Tetradiplon, or cloth folded in eight layers. This folded burial cloth of Jesus was placed inside a protective cloth case with a cut-out that revealed only the miraculous face image on the Shroud. In the first century this relic, with the Shroud hidden inside and the facial image visible, was venerated in Edessa as the Mandylion, the “Image of Edessa.”

The ancient history of the Shroud of Turin is closely linked to King Abgar and the city of Edessa. Edessa, now called Urfa in modern Turkey, was the capital of the Kingdom of Osroene, an early Christian kingdom located in Upper Mesopotamia between present‑day Syria and Turkey. Tradition holds that Osroene was the first state to officially adopt Christianity, making Edessa a major early Christian center.

According to the Abgar legend, King Abgar V of Edessa was suffering from the deadly disease of leprosy and around AD 30 wrote to Jesus asking Him to come to Edessa and heal him. Jesus is said to have replied that He could not come in person but would send one of His disciples. After the crucifixion and resurrection, the apostle Thaddeus (Addai) came to Edessa carrying the burial cloth of Jesus bearing a miraculous image, and when Abgar received this cloth—later identified with the Mandylion—he was healed.

Edessa remained a Christian kingdom during the reign of Abgar, but after his death in AD 55 the situation changed. When Ma’nu VI came to power around AD 57, Christian tradition says that persecution began and Christian relics, including the Shroud‑Mandylion, were threatened. To protect the holy image, Christians are said to have hidden the Mandylion inside the city walls, where it remained concealed for centuries.

Around AD 525, severe flooding damaged parts of Edessa and led to major repairs on the city walls. During this reconstruction, sources report that a cloth bearing the face of Christ—the Image of Edessa or Mandylion—was discovered hidden above one of the city gates. Once recovered, the image again became the most revered relic of Edessa, inspiring many early icons that copied the face of Jesus seen on this cloth. These icons helped shape Christian iconography of Christ’s face for centuries and are a key part of the argument that the Mandylion and the Shroud of Turin are the same burial cloth of Jesus.

Before the 6th century, artistic depictions of Christ often showed him as a clean-shaven, youthful figure. Seen here is a painting of Jesus with no beard, healing the woman who touched his robe. This painting is in the 4th century Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter in Rome. After the rediscovery of the Mandylion in Edessa (c. 525 AD) depictions of Christ suddenly and universally changed to match the unique features of the Shroud: the long face, long hair, and forked beard.

This dramatic shift in Christian iconography, from clean-shaven to the now-standard bearded Jesus, strongly suggests a widespread, authoritative template (the Shroud) became publicly available in the 6th century, over 700 years before the C-14 date.

Digital Information: The Shroud’s "Impossible" 3D Feature

One of the most amazing properties of the Shroud's image is the digital information encoded within it—a property that could not have been known or created in the Middle Ages.

The NASA VP-8 Discovery: In the 1970s, a Shroud photo was fed into a NASA VP-8 Image Analyzer—a device typically used for topographical mapping of surfaces like the Moon. 3D Distance Encoding: The VP-8 revealed that the darkness (intensity) of the image on the Shroud is directly proportional to the distance between the body and the cloth. This means the image contains perfect three-dimensional (3D) information. The Result: An Anatomically Correct 3D Map: This unique distance-encoding allowed the VP-8 to generate a non-distorted, anatomically correct three-dimensional (3D) topographical map of the face on the Shroud of Turin. The scientists running these tests were astonished, as this feature is considered physically impossible to achieve by painting, scorching, or any other simple contact method and suggests a momentary, unknown energy source from within the body created the image.

Any camera, whether a simple pin-hole or the most modern camera lens, captures an image based on light intensity, resulting in shadows and perspective.

The image on the Shroud has no shadows whatsoever. It is impossible to tell the direction of the light source because the image appears as if the light was directly perpendicular to every single point on the body simultaneously.

This lack of shadows on Turin Shroud image suggests the image was formed by an energy source that originated from the body itself and radiated outward.

The Forgery Challenge: Why a Medieval Artist Could Not Have Created the Shroud

The most powerful counter-argument to the 14th-century carbon dating is the sheer impossibility of forging the Shroud. To believe it is fake, one must believe a medieval forger possessed knowledge and technology only available today.

Imagine the supposed forger accomplished the following impossible tasks:

- He somehow secured a large piece of linen with the exact weaving pattern prevalent in the Middle East during the First Century AD—a technique unavailable in Europe 1,000 years later.

- He created a perfect, full-size human negative photographic image on the cloth *without shadows*. Crucially, this image contains digital 3D information only readable today by sophisticated NASA instruments used for planetary mapping.

- He included forensic details invisible to the human eye until modern times, such as the clear scourge marks of a First Century Roman flagrum (whip with small iron balls at the end) and the imprints of Roman coins from the time of Jesus placed over the eyes.

- He added pollen samples found only in Jerusalem, Constantinople, and along the Shroud's documented historical route—details only discoverable recently by high-magnification electron microscopes.

- He used rare human blood (Type AB) for the stains, ensuring they were congruent in shape and size with the stains on the Sudarium of Oviedo—a cloth unknown in 14th-century Europe. In his time, knowledge of human blood groups was non-existent.

- Finally, for geological accuracy, he included trace amounts of soil particles specifically from the Jerusalem area.

Considering the convergence of these impossible scientific, forensic, and historical feats, it is clear that no forger—not even the cleverest scientist today—could have manufactured the Shroud of Turin. The image formation remains a profound, unexplained mystery.

➡️ For detailed explanation about Carbon dating the Shroud of Turin using wrong samples to get a medevial age, see the page: Carbon Dating.

➡️More details about the existance of the Shroud of Turin much before the Carbon dated age, see the page Shroud before Carbon Dated age

➡️ See the 2,000-Year History of the Turin Shroud on the page: History of Turin Shroud.

➡️ Unique digital properties of the Shroud of Turin image, see the page Digital Properties of Shroud